Artificial intelligence (AI) is advancing into new tasks at a pace that seemed unlikely only a few years ago. Take software development: the SWE Bench benchmark tests whether AI can solve real-world coding problems. In 2023, leading models could solve just 4.4 percent of the tasks. By 2025, that number had surged to 71.7 percent (Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025). Things are moving so fast with AI technology that it is challenging to keep up, let alone prepare our society to adapt to such fast technological advancements. There might be vast implications for the modern education system. What skills should we teach to the next generation of workers?

AI systems have the potential to generate significant productivity gains and raise living standards. But rapid progress also brings uncertainty. At the level of individual jobs, the core question is whether AI acts as a complement to human skills or a substitute for them. History shows that transformative technologies often eliminate certain tasks and occupations while creating new ones. What makes the current moment challenging is the speed of technological advancements, raising urgent questions about how quickly the labor market and educational institutions can adapt.

In this blog, we take a brief look at what recent evidence suggests and what these developments may mean for jobs, career paths, and the broader economy.

AI is boosting productivity across many jobs, but the macro picture remains uncertain

According to recent experimental studies summarized by the OECD, productivity gains in real work settings typically range from 5 to 25 percent. These kinds of results, if applicable to the broader economy, can significantly increase the welfare of our societies in the long run.

Evidence from workplace experiments, however, shows that the impact of AI tools is highly uneven across workers. A widely cited paper by Brynjolfsson et al. (2025) examined the introduction of a generative-AI assistant for over 5,000 customer-support agents and found that average worker productivity increased by around 15 percent. Crucially, the gains were far from uniform: the least-skilled agents improved their performance by roughly 30 percent, whereas the impact on the most experienced agents was close to zero. In practice, the AI system helped lower-skilled workers adopt the decision patterns of top performers, narrowing the skill gap within the firm.

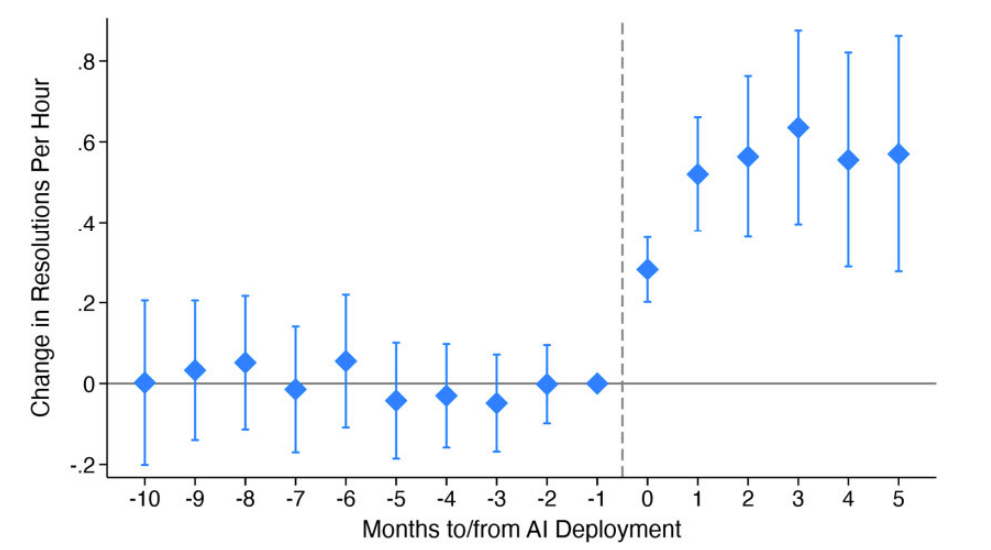

The figure illustrates the change in productivity before and after the rollout of the AI assistant. Before deployment (left side), productivity stays flat. Immediately after introduction (month 0), productivity jumps sharply and continues to rise over the following months. This pattern reflects the productivity increase observed in the study.

Fig 1: The effect of generative AI tools on worker productivity. (Brynjolfsson et al., 2025)

Currently, the results from experimental studies vary widely and relate only to specific tasks and tightly defined use cases. Still, as the technology advances and firms gain experience in integrating AI tools into their processes, it is reasonable to expect that the benefits of generative AI will spread across a broader range of tasks, occupations, and industries.

The academic literature does not yet offer a clear estimate of the overall productivity gains AI might generate at the macro level. What we do know is that information technologies tend to complement higher-skilled workers (Bresnahan, Brynjolfsson & Hitt 2002). Historically, digital technology has automated simple and routine tasks while increasing the need for skilled workers. If AI evolves in the same way, jobs that depend mostly on routine and easily defined tasks may face the biggest changes. Many of these tasks are common in lower skill roles and in some entry-level positions.

Early-career workers are more likely to suffer from the creative destruction of jobs

Recent empirical evidence suggests that generative AI does not affect all workers equally. Brynjolfsson, Chandar & Chen (2025) show that in occupations most exposed to generative AI, such as software development and customer support, employment among young workers aged 22 to 25 has fallen by about 13 percent after the introduction of modern AI tools.

Older workers in these same occupations have not seen similar declines. Employment among workers aged 35-49 has remained stable or even increased. This means that the reduction in headcounts is coming almost entirely from fewer young workers entering or staying in AI-exposed jobs. Occupations with low exposure to AI, such as health aides, do not show this pattern.

Similar patterns have also appeared in media reporting. For example, The Guardian ran a striking headline, “Gen Z faces ‘job-pocalypse’ as global firms prioritise AI over new hires,” referring to a survey by the British Standards Institution. According to that survey, roughly a quarter of business leaders believe that many entry-level tasks could be automated to cut costs. While the article’s tone is dramatic, it reflects a growing concern that firms may increasingly rely on AI tools rather than junior employees for routine work.

Herizon.io, a member of the Finnish Startup Community, has collected data on open positions in U.S. tech startups, and the results are striking. Out of thousands of postings, only about 1 percent are junior roles, and just 2 percent are internships. In practice, VC-backed startups in the United States are hiring almost exclusively mid-level and senior-level talent.

Finland is likely to face similar challenges for young professionals and entry-level workers. At the same time, history shows that people often overestimate the short-run impact of new technologies and underestimate the long-run effects. We may see significant shifts in labor markets, but these changes are likely to unfold gradually. That slower pace may be helpful: societies struggle to adjust when disruptions happen too quickly, often leading to higher unemployment or long transition periods for entire cohorts.

What Should Finland Do?

The trends highlighted in this blog raise an important question: how should Finland prepare its workforce for an economy where AI tools rapidly automate routine tasks and reduce demand for traditional entry-level roles? If junior positions shrink while skill requirements rise, Finland must rethink how young people gain work experience and acquire the competencies employers now expect.

Fresh data from Herizon.io, based on more than 11,000 open positions in U.S. tech startups, shows that only 1 percent of vacancies are junior roles and just 2 percent are internships. Almost all open positions require mid-level or senior-level competence. While Finland’s labor market is not identical to Silicon Valley’s, it is difficult to imagine that these patterns would remain contained abroad. If U.S. startups are already shifting away from junior hiring, similar pressures are likely to reach Finland as AI tools become more widespread.

This puts education and training systems at the center of the discussion. According to Herizon’s experience working with hundreds of interns each year, schools are already behind: curricula update slowly, practical work-life skills are uneven, and students often reach graduation without exposure to the competencies that employers actively demand. Their analysis shows that skills such as AI, machine learning, backend engineering, and platform engineering are among the most sought-after—yet many Finnish higher education programs still emphasize older content or theoretical knowledge with limited practical application.

To avoid a growing gap between graduates and job opportunities, Finland may need to rethink how it prepares young people for work. This could include:

- More internships and practical training, integrated early into degree programs so that students build real work experience before graduation.

- Closer collaboration between schools and employers, ensuring course content evolves as quickly as industry needs.

- Faster curriculum updates, especially in applied technical fields where tools, frameworks, and competencies change rapidly.

- A stronger emphasis on work-life skills such as teamwork, communication, problem-solving, and navigating modern digital tools.

AI will create new jobs and opportunities, but the transition period may be challenging, especially for those entering the job market for the first time. The choices we make now will determine whether young workers face shrinking opportunities or whether Finland can turn this technological shift into an advantage.

Youssef Zad

Chief Economist

Finnish Startup Community

Mari Lukkainen

Founder

Herizon